Sarakin

Sarakin

Loan sharks are moneylenders who offer unsecured loans with extremely high interest rates. Since most countries tightly regulate moneylending, they often operate outside of the law and harshly enforce debt collection from their borrowers.

In Japan, private moneylenders are regulated far more loosely than banks, needing only to follow bare minimum requirements such as prefectural registration. Thus, they can operate with some impunity so long as they meet regulatory standards. These legal loan sharks are called sarakin (サラ金)—a portmanteau of "salaryman” (サラリーマン) and kinyu (金融), meaning "loan" —and are notorious for having their rates skyrocket within short periods of time.

The number of sarakin borrowers rose sharply around 1992, after the collapse of Japan's housing bubble. This event began an ongoing era of economic stagnation once known as ushiniwareta juunen (失われた10年), or The Lost Decade, but now referred to in the plural Decades. Japanese banks grew stringent about offering loans, all while unemployment and economic insecurity soared. Japan’s most desperate—particularly small business owners, people with poor credit scores, and those struggling with addictions—found themselves turning to sarakin for financial help, and that trend has continued ever since.

Taking out loans with sarakin has shackled roughly 14 million people, or 10% of Japan’s population, to a cycle of endless debt and relentless harassment. During the start of the Lost Decades, sarakin were closely linked to yakuza crime syndicates. They would aggressively harass borrowers, even showing up at their homes, workplaces and family events. Borrowers' ensuing distress has come to be called sarakin jigoku (サラ金地獄), or “loan shark hell.” It's not unusual for their mental health to deteriorate, as they yield a high suicide rate.

Although regulations against sarakin have increased in response to public outcry, their societal consequences remain a prominent social concern in Japanese politics.

Relevance to Eyeshield 21

Relevance to Eyeshield 21

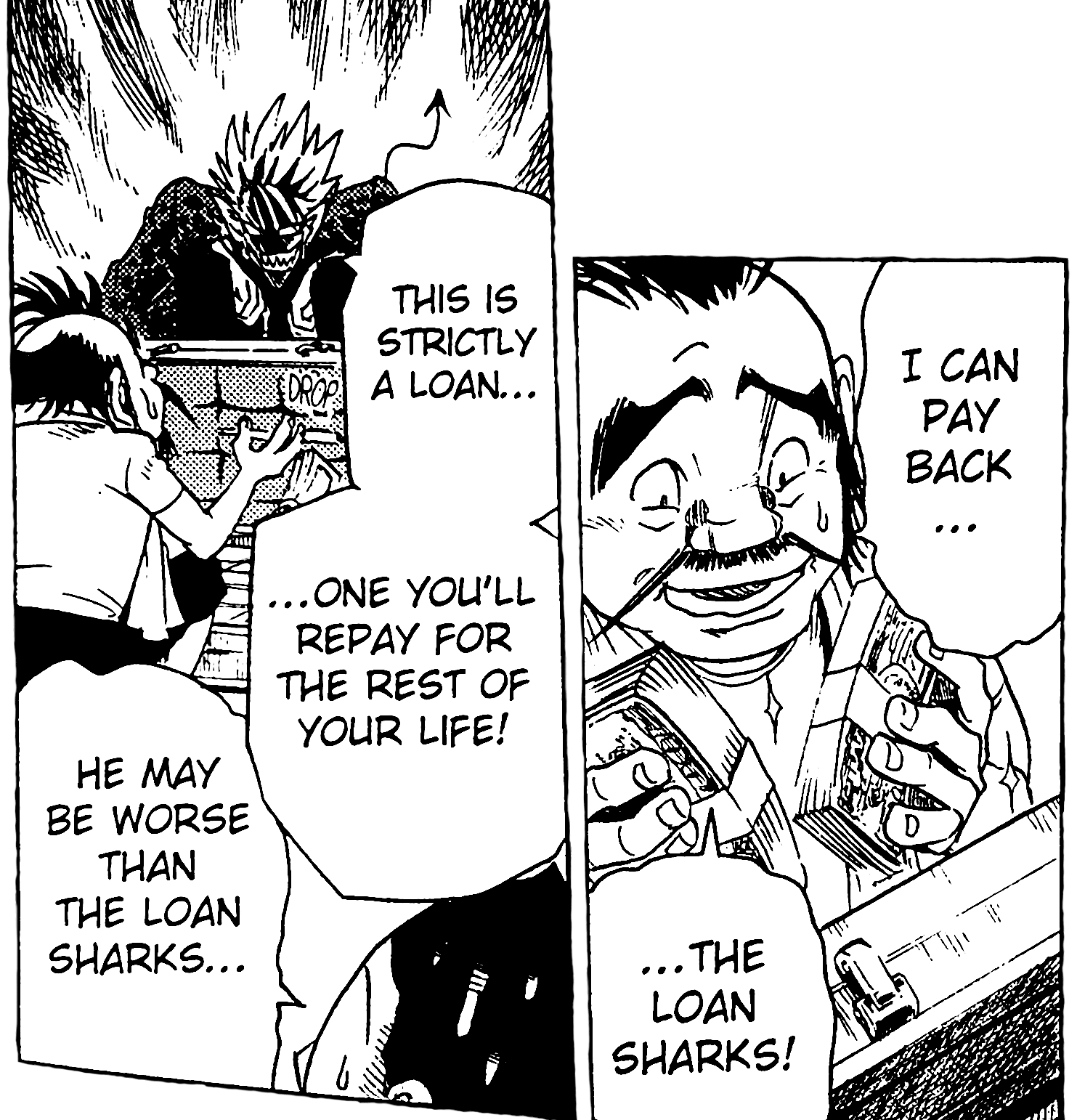

Sakaki Doburoku, coach for the Deimon Devil Bats, accrued 20 million yen (roughly 200,000 USD) in loan debt three years before the start of the series.

Judging by the unusually large amount—even with his frivolous spending habits—and how he fled Japan with no intent to return, it’s possible that Doburoku took out loans with one or more sarakin. Hiruma’s sweeping jackpot during the Devil Bats’ trip to Las Vegas paid off all of these debts, but in turn made Doburoku a debtor to Hiruma instead.